Today we are sitting at a marble “Tulip Table” at the New York City apartment of a mutual friend who is also a musician and prolific writer. The small vestibule is crammed with harps. I also see a cello, a violin, guitar, full-sized keyboard, three recorders. Nico has brought his own, el arpa llanera, also known as the Colombian Harp. It’s a beautiful instrument, a bit smaller than the classical harp, with 32 chords.

Though his English is good, Nico and I slip naturally into Spanish, to the intimacy of our native language.

El Niño Orquesta

Nico, when did you begin playing music?

I was a four years old. I remember the teacher at school—an older woman who moved between us with an accordion while we played on our flautas dulces, plastic recorders. [Literally, this means sweets flutes.] We played songs from Colombia’s coasts on the Atlantic and Pacific. We were in a school for children of employees of ETB, Empresa de teléfonos de Bogotá, the city’s phone company. My mother worked there as operadora de reclamos, like customer service here. The company was famous because it offered so many free benefits to its employees and their children. Healthcare. Travel to school and work. Lunch. Uniforms. Also a vacation club. They wanted students to have art experiences.

When I was seven I moved from the recorder to folkloric percussion. Small drums, maracas, el chucho. That’s the hollow, sugarcane stick with seeds inside. This was the beginning of my adventure with Colombian percussion. At twelve I began with the clarinet, and was lucky to study with Nacor Barón who became director of the Orquesta Lucho Bermúdez, famous in all of Latin America for Colombian folkloric rhythms, boleros, cumbias, porros, and merecumbé. The orchestra would invite me and a few other children to play the clarinet during their band rehearsals. I was like “el niño consentido,” the teacher’s pet. They were very kind to me.

When did you know that music would be the love of your life?

A smile spreads across Nico’s face as he begins to remember. Si. Fué así. Three of us children studying the clarinet were invited to play with the famous band at the Jorge Eliécer Gaitán theatre, one of the most important performing spaces in all of Colombia. I was thirteen. The orchestra director said, “We will all begin together, but there will be a moment when the orchestra disappears behind you. And you boys will be playing solo.”

Having a roomful of people—a thousand people—right in front of me and seeing their happiness as they listened to us three. I knew then that this was for me. Curioso, no?

And the harp?

When I was fourteen, a distant cousin from the eastern plains of Colombia appeared at my house with another cousin who played the harp. “Ese es ‘el niño orquesta,’” they cried out, “the boy orchestra! Let’s make you a bet. If you play the harp for a year, I will give you the harp. If not, you’ll return it to me.” They left the harp at my house. I didn’t have a teacher, so I practiced empírico by ear. Mi papá era amante de música llanera, and so I knew the songs by heart. Música llanera usually involves harp soloing, a cuatro (a four string guitar), fast maracas, also voice and tapatéo.

A teacher at my school told me about a new academy for children and adults called Academia Llano y Joropo. He took me to see it after school. There were two huge rooms and about forty harps. The teacher iba dando ronda, he’d walk around the room from person to person. People of all ages playing at the same time. “Pues aquí te espero. I’ll be waiting here for you,” he said.

I’d go to my school from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m, and from 5 to 6 p.m. to the new academy for harp. I had the unconditional support of my mami, mi super-mamá! In my school at ETB they didn’t give us homework. All the learning was experiential. To understand the concept of Newton’s law, we’d throw an apple around. English was hard for me. We studied physics, electronics, telecommunications. I would take tests, rehearse my music, and travel.

After about a year of studying the harp, I began to participate in music festivals. I would win an award most times. For example, at the Festival Castilla la Nueva I won “mejor artista” in my category as well as “mejor conjunto,” best artist and musical group. I had two brothers, an older and a younger one. The younger one was mi maraquero. He would join me at serenatas, birthday parties, and weddings. He was also studying at the academy. I was earning some money from the time I was fifteen.

The Bet

So life in Bogotá was lush with music. Why then did you come to the United States?

It all happened because of a bet. The really wonderful Berklee College of Music in Boston would send their musicians to other countries to audition students. Typically they went to Argentina and Ecuador, and in 2012 was the first time they came to Colombia.

By now I’d been studying music for seven years at the Academy of Arts at the Universidad Distrital in Bogotá and needed thirteen more months to complete my requirements. A singer at the University piqued my interest. “Let’s both audition,” she said. “If we get to the United States, we’ll eat a bag of Cheetos at the entrance to Berklee.”

I did very well at the audition—es la verdad. I won a scholarship for half of my tuition for the entire career, with opportunities to add scholarships toward the full tuition. It’s usually a four-year program. I completed it in two and a half to three years. Near the end of my schooling I was able to win a BMI Foundation scholarship. I am very grateful to Oscar Stagnaro, an amazing Peruvian musician.

What other subjects did you study at Berklee?

I did Contemporary History, Sociology, the Civil War in the US. How for example, the music of the Delta and New Orleans provided a transformative expression of the times. I studied the Celtic harp and the music of Ireland. The Celtic harp also has its origins in folkloric tradition. As with the llanera, there are variables, but it is accompanied by a singer and almost always by dance. The harp and the dancers are in conversation. A soloist harp is really something new.

My friend was not selected at audition, but she is still an outstanding musician. I ate the bag of Cheetos alone in front of the school.

“Soy un bicho raro.”

Nico, for the uninitiated, can you explain the folkloric music of Colombia?

It’s music of oral tradition. There are no European annotations, what is called “theory.” Folkloric music is improvisational and relies on its melodies. Because Colombia has a diverse geography, and cities even are separated by mountains and rivers, the folkloric expression is very variable. The music and the lyrics change, but the content always involves flora and fauna and love, and always exists within the socio-political context of the day.

You sound like a professor.

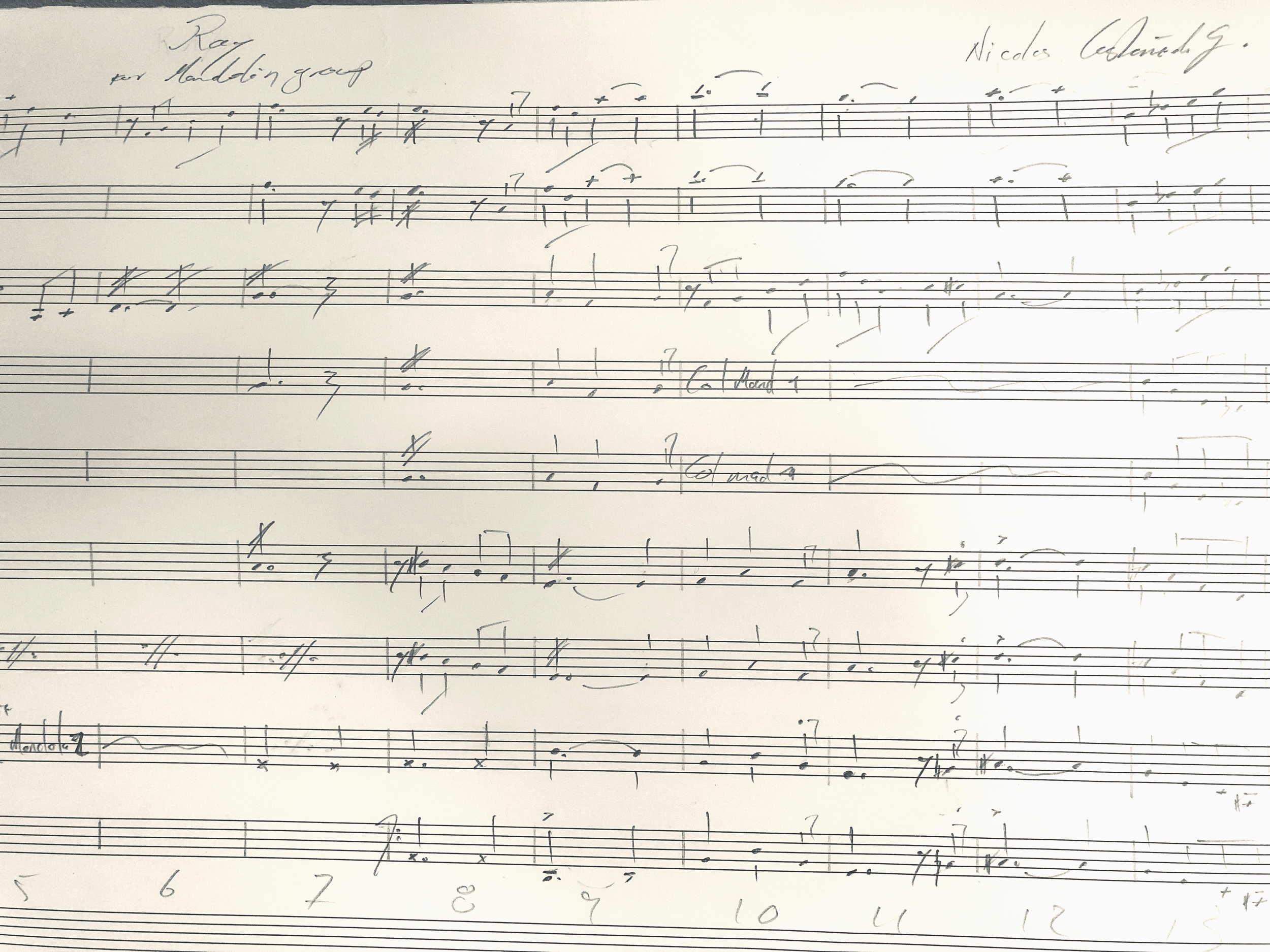

There has always been an attempt to write this music in a more academic way, to play it in church choirs and such. This is one of the things that excites me, creating music annotations not in a European way but in a way coherent with the tradition. Academic attempts in the past have not been able to capture folk music completely.

Soy un bicho raro—an odd kind of bird. I first learned everything empirically. When there was no harp teacher at the Universidad Distrital, I decided to change my emphasis to classical composition. There I negotiated with professors to let me apply the concepts of classical music to Colombian music, so I began studying theory early. At Berklee I studied improvisation in an academic context. I tried to use my knowledge of classical music, jazz composition, and the rich exposure to other students at Berklee to create Colombian musical phrasing in my EP called Renacer, meaning Reborn. I want to conserve Colombian traditions and mix them with swing and jazz from the United States.

So, creating mezcolanzas de cosas fundamentals is one of your aspirations. The other is to return to Colombia with new projects. What are these?