We Live in an Immense World

I recently read Ed Yong's An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us, a big, thick book that I had to prop on my pillow at night. Though it was not easy to read, I am left with bits of knowledge, much of which I will forget, but that leave me with a speechless wonder about this earth that we share with billions of species.

The driving idea is that the earth is full of sights, sounds, textures, vibrations, smells, tastes, electric and magnetic fields, but species can only tap into a small portion of this. Each species lives in its own sensory bubble, it's Umwelt, or perceptual world.

So, I don't have to travel to Africa or the Grand Canyon to experience the wonders of nature. Here in my backyard I can know that bees and other insects taste a flower with their feet, (like a mosquito that tastes your warm, delicious skin with its feet, before it bites). That the owl that I saw months ago makes use of its stiff feathers to funnel sounds into its ears that are slightly asymmetrical and help it hear sounds on vertical and horizontal planes. Watch out, ratoncito! That the spider's vibrating web acts as an extension of its senses. That my sons' Covid pups experience smells as "a shimmering environment where smells diffuse and seep, flood and swirl."

Do you know that snakes smell with their forked tongues?

"The idea of Umwelt, tells us that all is not as it seems...that there is light in darkness, noise in silence, richness in nothingness. It hints at flickers of the unfamiliar, of the extraordinary in the everyday." —Ed Yong

More poignant than the differences between species are what we humans are causing to happen that harm the well being of other creatures, disorienting migrating songbirds with our penchant for light, sound pollution of our seas, and so much more. An Immense World is an important book if we want to understand and make changes to benefit our wondrous Earth. The book has been a bestseller since it was published, mid-2022. It's good to be able to compare notes with others and push through all the detail, so read it with a friend.

Ed Yong's earlier book: I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within us and a Grander View of Life is next?

The Museum of Natural History

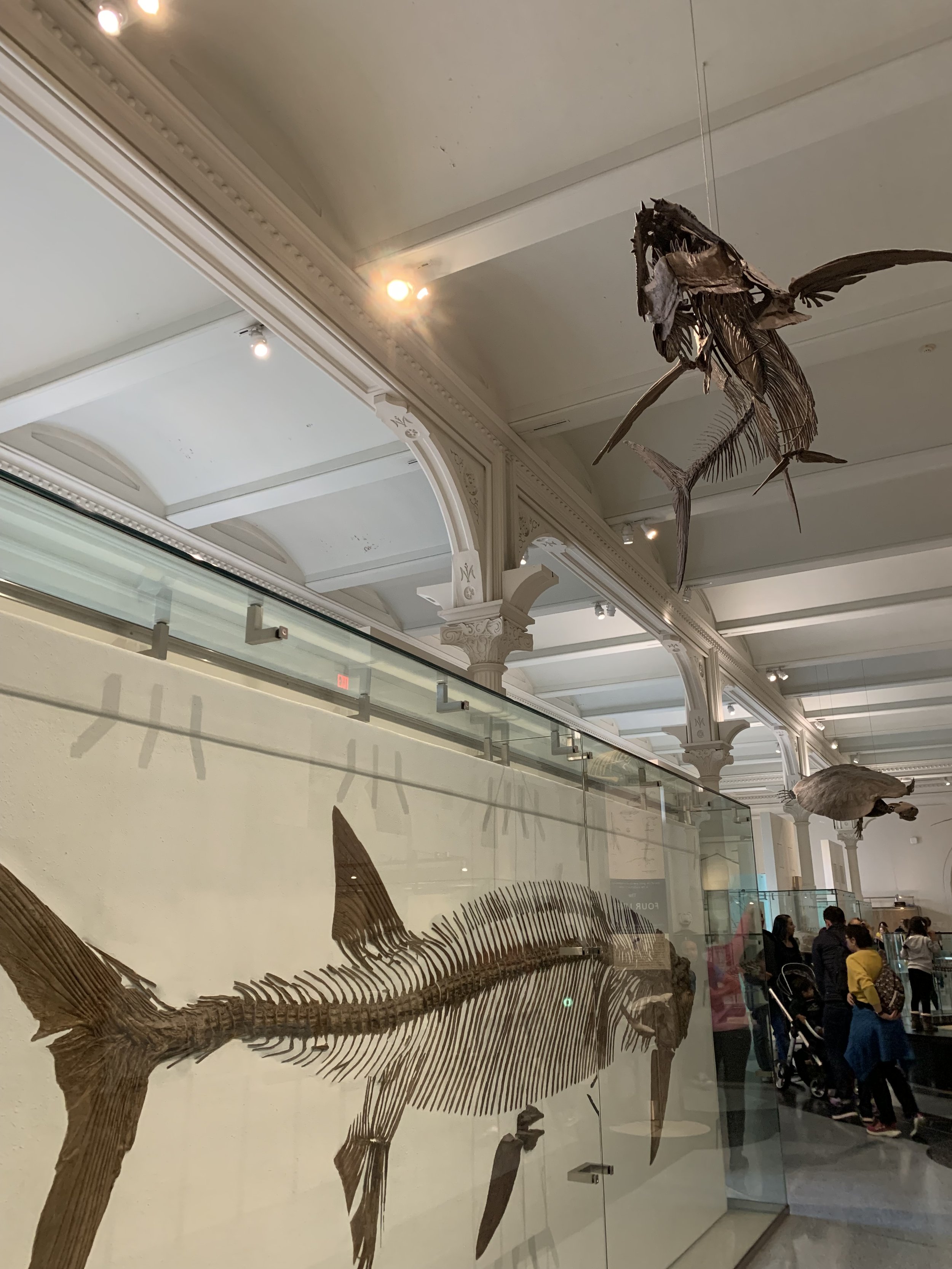

When our youngest son, wife, and teenage sons paid a visit to us in New York, we made a pilgrimage to the Museum of Natural History on the upper west side of Manhattan, only half a block from where we lived long ago. On snowy winter days, I'd take our two boys to play in the empty marbled halls surrounded by dioramas behind sturdy glass with lifelike animals in their natural landscapes; the museum was our playground.

Since those days the museum has grown into a powerhouse of knowledge about the earth and all living things—with the understanding that everything within it is dead. Creatures excavated or once killed and stuffed; or recreated. Humans, clearly, are in charge.

I had an epiphany in the Hall of Vertebrates. I noticed among skeletons dominating the center axis, or behind glass, or hanging above, a recurrence of one form—a curved and spiky cage of bones. Over and over and over. "Oh my," I said to my guffawing daughter-in-law, "we all have ribcages!"

Do you know the evolutionary function of ribcages? They expand to pull in air. Do you know that snakes have two sets of ribs for every vertebra? They can have as many as 200 sets of ribs. How many ribs do humans have?

What they said to me

With teenagers and almost teenagers in constant flux, you want to pay attention. What are you thinking beautiful child? What does the holding back mean?

"Grandpa, sounds happy. Is he happy?" —my fourteen-year-old granddaughter.

I smile, and she adds, "a happy wife makes a happy man."

"You can look at a lightbulb as lighting a dark room, or you can see it as sucking in the dark."

—first-born grandson, hiding under hair.

My pen hollows out the whiteness on this page.

What is my obligation to protect our beautiful Earth?

What am I willing to do?