This interview is a continuation of my Soy/Somos conversations with Latinos in the US and others living in a hybrid world. This is who I am/This is who we are. If you’d like to receive future Soy/Somos posts, please contact me here.

Carlos wore a long sleeved black “t” and a Panama hat. We were meeting, New York/Los Angeles, compliments of cloud technology. I excused myself to collect my Panama hat and placed it at a rakish angle on my head. Carlos laughed, and we began.

Carlos Carrasco, with a long and rich filmography, is an American actor, Indie director, and producer. He was born and raised in Panama and is founder and Executive Director of PIFFLA, the Panamanian Film Festival in Los Angeles. It was thrilling for me to hear Carlos’ stories about growing up in Panama—distinct from mine but deeply resonant—and to learn about his experiences in the worlds of moviemaking in New York and in Hollywood. Carlos talks about the narrow limits he faced in the industry as an Afro-Latino actor but sees hopeful changes in recent years. Shadowing my every question to Carlos was this one: Can you ever leave your childhood home? His answers are woven tightly in the fabric of our conversation.

Carlos, what are you loving to do right now?

In this particular moment in history that we are living through? The thing bringing me the most joy right now, today, is looking forward to closing on an apartment purchase in Panama. Visualizing myself taking possession of this property, enjoying the time that I am actively planning to spend in Panama moving forward.

Is the property in the city or in the countryside?

Right in Panama City on Avenida Balboa overlooking the Cinta Costera. … going for a stroll on the Malecón, looking at Casco Viejo, and stopping for a raspado….

Carlos, you are making me nostalgic!

Bueno, the real issue is that after all these years of living in the United States as a transplanted Panamanian, becoming a proud American citizen, and really enjoying my time here—as a student (I totally loved my years in college) to pursuing my profession where I feel I’ve achieved a degree of success, even notoriety—I’ve reached a moment where I actually don’t feel comfortable here. I’ve been thinking for the last couple of years that it’s time to return to Panama.

Panama City - Plaza Catedral in Casco Viejo, the old colonial city.

This is momentous! Is it too personal to ask…? Why don’t you feel as comfortable here? Can you talk about that?

I can. I came to the US as a young man; I think I was twenty. I happened to come during a historically tumultuous time. I am talking about the late 60s. I lived through that whole era of artistic and social upheavals of the 60s and 70s. Being an impassioned college student, I participated in the protest marches, the anti-war movement. The civil rights struggle was frankly new to me when I first came because, without sounding Pollyannish or pie in the sky, growing up in Panama gave me the blessing of not feeling conscious of racism and racial compartmentalizing. Though, I know there’s no such thing on the planet as the absence of racism.

IT’S TOTALLY DISPIRITING

The arc of history can bend slowly but tends to bend upwards. I was here for the passage of the Civil Rights Acts, the end of the Vietnam War, the legalization of abortion, women’s rights, the recognition of minorities. I participated in the change and had hope for this country. To see that evolution deflated in the last several years is totally dispiriting.

My generation was invested emotionally and philosophically in this country, and seeing it eroded now, permission granted to behaviors that are unsocial, unconstructive—all of that roaring back. It’s time for a new generation to take its bow.

My wife and I spent this January in Panama and experienced the very tangible feeling of equality, of embrace. You walk into a room and people say “hello,” not just some kind of blank stare not knowing what’s behind it. I don’t want to live that way.

Can you pinpoint what there is in Panama that contributes to this good feeling?

We have all been living through a monstrous pandemic. At the airport in Panama the first thing we noticed was that everybody is wearing their mask. Observing social distancing without chest pounding and cries for freedom. A society coming together to address a national challenge. There is no political whatever. You immediately get the sense that we all row together. What I find happening here is preposterous! A false ideology.

Then of course there are the culturally specific things—the food, the customs, and the beauty of Panama physically, the geography of it!

There is not a single place in Panama where I would feel unwelcome. In all the years that I’ve lived in the US, I have to admit, I haven’t felt that sense of ease and comfort. Parts of the US are off limits for me. I can’t trust how I will be received. You compartmentalize this thing for years, for decades. Why exactly?

LOS VICENTINOS

Let’s go back in time Carlos. If I’d met you in Panama as a boy, what would I see?

I’d be in a little school called Colegio San Vicente. I went from primer grado to I think, then, quinto año. Eleven years. The whole time with the same kids. There’s a healthy portion of us who stay in touch—calling ourselves “school brothers and sisters- Los Vicentinos.” We had the Catholic monjas and the priests. It was old-school Catholic school where the nuns hit you with rulers and the priests beaned you with erasers. Ours were Irish monjas from the missionary order of Maryknoll and the priests were from the Vincentian order. Great people.

My earliest memories as a kid are of my maternal grandparents. I didn’t meet my parents until I was 6. They never tell the kids what’s really going on. My older brother and I were raised until we were 6 and 8 by these abuelos. I found out later that both my parents got advanced degrees in the US. My mother, a Master ‘s degree in English at the University of Michigan; my father, an MBA from the University of Minnesota. This was in the early 50s. So it's possible that in my early childhood they were away at school. My grandfather, Alphonse Mandeville, spoke no Spanish because he was originally from St. Lucia in the Caribbean and my grandmother Maria Luisa Justiniani was a Panamanian who spoke hardly any English. She was of Colombian descent.

So we grew up with the mixed languages: Pipo would discipline us in English, and Mima would spoil us in Spanish. Then we went to Colegio San Vicente with the Irish nuns. Most of the education there was in English.

People don’t realize how very mixed Panama is.

That’s my point. I grew up like that. Colegio San Vicente was our world. We were everything. We had los morenitos, los blancos, los negros, los rubios. My best buddy, Jorge Chen, was Chinese. We used to go fishing in the Canal together. It was everybody mixed together. To step into another culture where this was not a given was a real revelation to me.

“STREET”

And then you left. Take me through that.

I came to the US on an acting scholarship. I had started college at the American junior college in what was then the Canal Zone, a ten mile wide strip of land surrounding the canal and under US jurisdiction. There I was blessed to meet a teacher who literally changed the course of my life. David Lommen, an American teacher, became my first real drama teacher, mentor and friend. He identified a scholarship program at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri, and guided me through the application process. I was very fortunate and won a scholarship to this private women’s college where they had an allowance for a small number of male students in the performing arts department. There were eight of us and 2,000 of them.

After Stephens, I made it my business to keep applying to universities in order to maintain my student visa. I managed to keep that going for my first six years in the States until I finally got my green card.

The world of academia is in its own way a closed environment. You are in a cocoon. It was a more liberal, a headier environment. So I was fine. It was not until the time that I stepped into the professional world that I started feeling the impact of some of the things I’ve named such as marginalization and ethnic categorizing.

Relaxing on the set of Speed released in 1994. Carrasco is on upper left

In academia, preparation for working in the entertainment industry tended to ignore what was going on in the real world. So I spent the last three years of school honing myself as a classical actor, to do Shakespeare and the classics. When I did finally step out into the environment of the professional industry, I had a really harsh wake up.

I’d go to auditions, speaking in my trained voice [Carlos deepens his voice, speaks with an English accent when he recounts this] with my perfect enunciations. I was almost laughed out of the park. I could not get arrested. And all the material I was handed to do was “street,” the violence, the bad guys. I’d spent three years playing Romeo in Romeo and Juliet in the Midwest, then I go to New York and I’m handed the drug runner, the thug.

So you run the gamut of reactions from confusion to realization that morphs into anger and frustration. I had to dumb myself down in order to start securing work in the industry. Because the diction and expression that I’d trained myself into was a path straight to the exit. I had to learn “Puerto Rican street” to get work. That led to what became my on-camera trajectory. “He’s big—he’s dark—he’s Latino—he is a bad guy.” And you go, wow, if I want to work, that’s what I must do. So you bite the bullet and learn how to shuffle.

Then I moved to LA and had to learn a whole new thing. Now I had to be a Chicano “pachuco” to get work in Los Angeles. “Orale, vato, let’s slide in the lowrider and go cruising for rucas….”

OTHER PANAMANIAN ARTISTS

While in New York, Carlos, did you meet or work with José Quintero on Broadway? Otro Panameño… considered the quintessential director of Eugene O’Neill’s plays.

The closest I came to José Quintero was my one-time role on Broadway at the Circle in the Square theatre where he had many successes when directing in New York. There are famous Panameños all over the place in the industry. Do you remember a movie called Alice’s Restaurant?

¡Si, claro!

The Arlo Guthrie song that was made into a movie. The actress who played Alice es Panameña, Pat Quinn, who lives in Panama now, in El Valle. That’s another Panamanian who went to the US and scored a few hits. Alice! Her brother, Bruce Quinn, never left Panama and was the big theatre producing guy in Panama. He was responsible for the huge, annual United Fund Show, always a big musical, My Fair Lady, The King and I….

The last one I was involved with the summer before I came to the United States was West Side Story. I played a Shark. Rubén Blades was a Jet. We were both in the chorus. We became buddies then, and after rehearsal we’d roam the streets of Panama deep into the night and go to little jazz clubs and stuff. Rubén would get on stage and jam with the musicians doing Frank Sinatra and Bobby Darin renditions. I’m still his biggest fan.

PIFFLA - PANAMANIAN FILM FESTIVAL OF LOS ANGELES

Tell me about your film projects at the Panamanian Film Festival? Do you see bringing to Panama that kind of focus?

I started that film festival about eight years ago responding to the reality that there was a growing film industry in Panama and that Panama is evolving as a film destination of its own. The filmmakers in Panama are still on a learning curve, but they’re getting it. There’s a tremendous feature film that almost made it to the final Oscar nomination list. Have you seen it, Plaza Catedral?

You know, it was in Queens during this time of Covid , and it became complicated to get there. I definitely plan to see it in a future venue.

That particular filmmaker, Abner Benaim, I rank him right up there with anybody on the film stage. His work is very accomplished, complete. So for me, starting a film festival in Los Angeles was an attempt to share what was going on in Panama with the industry here in the US, to expose the filmmakers on both sides to the talent and to potential collaboration between the two universes.

Over the years I’ve developed relationships on both ends. It would be an easy transition to take my base of operations from Los Angeles to Panama City because I would not be arriving as a stranger.

At this stage in my career I am looking for artistic expression, an opportunity to grow as well as opportunities for mentorship. As you get older you get a lot of rewards from sharing what you know. When you get to be an old fogey, you know a lot of stuff.

…before you start forgetting it….

So it’s important to start sharing it before it’s all gone. These are the things that bring me joy now. The last few years I’ve been doing projects with Juan Escobedo, a Mexican-American writer and director who works with young people, especially in the barrios. He is based in East Los Angeles and runs the East LA Film Festival. We’ve joined forces in the last few years. We help young people create their own small films. We expose them to the different job opportunities in film, from writing, to wardrobe, to catering, and we reserve blocks in our festivals to screen some of their work.

What is your most famous role, Carlos?

BLOOD IN BLOOD OUT

It’s one of the great ironies of my life that, apparently the most memorable thing I am leaving behind is being an Original Gangsta. I did a film in the early 90’s, Blood In Blood Out, that has developed a major cult following within Chicano culture. It’s a phenomenon now, passed on from one generation to the next who study it, view it repeatedly, and memorize the dialogue. I call it my Rocky Horror Picture show.

No la conozco

Well you are not alone. A little history about the film. This was made in the early nineties by Taylor Hackford, a famous Oscar-winning director known for An Officer and a Gentleman, where he discovered Richard Gere, and many subsequent top-tier films like Ray, with Jamie Foxx. He was Director of the Actors Guild. He also, incidentally, is married to Helen Mirren.

Blood In Blood Out is a huge epic film released in ’93. It’s set in the Chicano world. On the surface people say it’s a gang movie, but it’s not that. It’s about family; it’s about loyalty and tradition, which speaks to why it has endured. It was the first time the vibrancy and depth of that culture was reflected on the big screen.

The movie was in post-production when the LA riots happened and, because it features gangs in LA and in the prison system, it became a hot potato. It was in the wrong studio, too—Disney—an odd place for this film. In those years Disney had created this adult division called Hollywood Pictures. There were incidents when they test screened the movie, pushing and shoving in the lobbies between different factions. The studio got cold feet. They marketed and released the movie, then pulled it away. They changed the title—"Oooh the title is too bloody.” They finally re-released it two weeks before Terminator 2. The movie then sank like a stone. But, once it was released on video, it started to find its audience.

Thirty years later, it’s become this major rite of passage in the Latino Community. People say, have you seen Blood In Blood Out yet? It’s remarkable to me. Popeye, the character I play in the movie became a fan favorite. A gross, outrageous character. The fans love him. In consequence, they love me.

If you google Popeye in Blood In Blood Out, you will discover this enormous black market in merchandise. There are T shirts with my face on them, coffee mugs, lotería cards…. I find it ironic that this little “chombito” from Rio Abajo in Panama comes to the States and ends up being this icon of Chicano culture. For a long time I pushed back against it. All I am saying is, I was here from Panama to be Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier, and when I go back, I’ll go as this figure from Chicano culture.

Lately, I’ve been going to meet and greets for the movie. A promoter convinced me that there is this large fan base out there anxious to meet me, and I’ve discovered he was right. I’ve also discovered that I enjoy meeting these folks. You develop this curiosity. I ask, “What does this mean to you?” and their answers can be quite moving. From teenagers to grandparents. I saw a photograph of someone who’d tattooed my face on their thigh. I go “Whoa!” Everyone wants me to say their favorite line from the movie. And they ask me, “Are you all right?” “You look good.”

It’s not just Latinos. The cult of this film is actually worldwide. I’ve been stopped in Africa, Italy, Peru, the Hopi reservation—you name it—over this film and this character. My grave is going to read, “Here lies Popeye.” I’m serious.

LATINOS IN FILM TODAY

Let’s go back to where we started, Carlos. I am going to ask you a big sloppy question: What is happening with Latino actors in the business of movies today?

There has been considerable change since my early days. The breadth of character types available to Latinos has expanded from maid, prostitute, gangster—to doctors, nurses, detectives and heroes in general. The increased presence of Latinos in executive suites, in producing, writing and directing capacities, has made a tremendous difference. It is hard for the industry to ignore the award winning work of directors like Iñarritu and Cuarón, the star power of Penelope Cruz and Javier Bardem, both Spaniards, Oscar Isaac, and recent Oscar winner Ariana de Bose.

The last name is particularly significant to me, as that young lady has raised the consciousness about an ignored segment of the Latino population—the Afro-Latino, a concept that either through willful ignorance or laziness was non-existent in the industry until recently, leaving Afro-Latino performers trapped in the dilemma of having to try to “pass” for American Blacks in order to secure employment. This is a huge revelation that has come too late in my own career. Then, of course, there’s Lin Manuel Miranda, who single-handedly is rewriting the entire playbook by the strength of sheer talent.

COMING HOME

Carlos, is there anything you would miss about the United States if and when you settle in Panama for most of the year?

People. I’ve made some very good friends in the course of the years I’ve been here. But today, at this moment, I would have to leave it at that. I can’t think of, Oh it’s the fall, let’s go to Cape Cod.

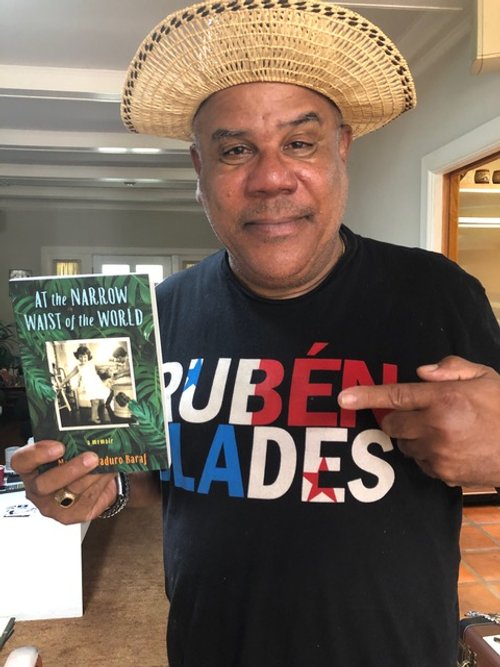

Carlos surprised me with this photo, holding my memoir, At the Narrow Waist of the World.

Me has alentado a hacer una visita a mi país.

When were you there last?

I have a very dear cousin who died in November. I went for the prayers and to be with family . I came back feeling profoundly blessed. Because you are there with everybody. There’s so much love.

Maybe we’ll see you in New York?

We are overdue for a trip to New York. In fact one of the things I would miss about the US is New York. Rochelle of course is from there. I have a lot of good memories. Plus the thing of being in New York.

Are you playing your guitar these days?

Every day. Every day.. When you say, what will I miss? One of the things I do here is jam with like-minded old fogeys. We sit around and most of the content is blues and folk and blue grass. I don’t know that I’d find a group like that in Panama.

Gracias, Carlos. Ha sido un gran placer conversar contigo.

Can you ever leave your childhood home?

Marlena Maduro Baraf immigrated to the United States from her native Panama. She is author of the memoir, At the Narrow Waist of the World, and co-author of Three Poets/Tres Poetas chapbook. Her writing credits include, Ms. Magazine, Huffpost, Poets Reading the News, and elsewhere. She’s always on the lookout for Latinos and others living hybrid lives.